Subscribe to Art + Ideas:

“We hear the security guards talking to one another on the walkie-talkie, saying that there’s a man on the line saying that he has a stolen painting. And I wish somebody could’ve seen us, because we just stopped our conversation and Jill’s eyes got big, and she said, ‘Oh, my gosh, are we gonna remember this moment for the rest of our lives.’”

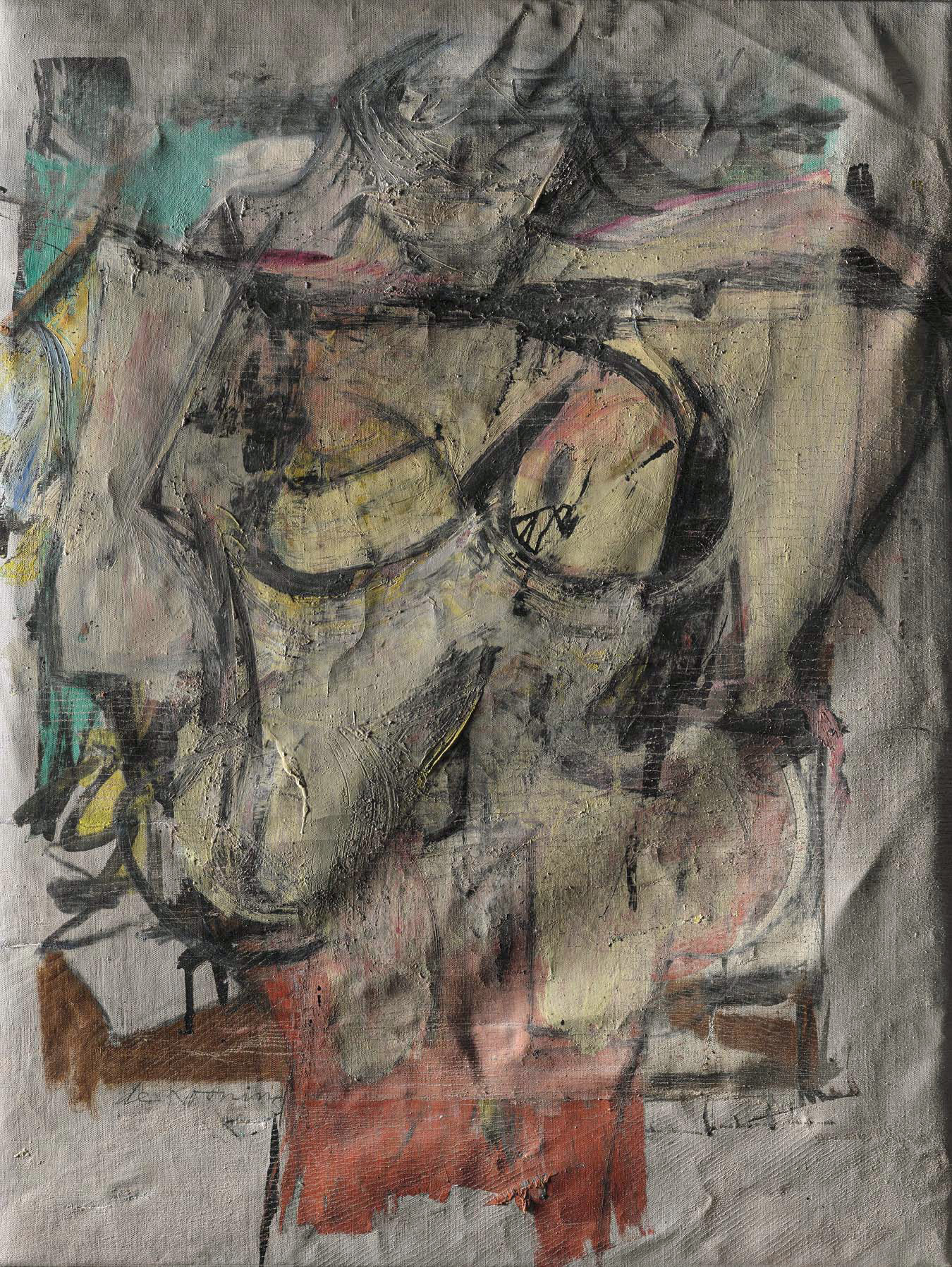

On the day after Thanksgiving in 1985, two thieves casually entered the University of Arizona Museum of Art (UAMA). They strolled out minutes later with Willem de Kooning’s painting Woman-Ochre. Without security cameras or solid leads, the trail to find the stolen painting quickly went cold. In 2017, however, the artwork turned up in an unlikely place: a small antique shop in Silver City, New Mexico. After more than 30 years, the work was finally returned to the UAMA, but it was badly damaged, due to the way it was torn from its frame during the heist and how it was subsequently stored and handled. The UAMA turned to the Getty Museum and Conservation Institute to help conserve the painting.

In this episode, UAMA curator of exhibitions Olivia Miller and Getty Museum senior conservator of paintings Ulrich Birkmaier discuss Woman-Ochre’s theft, recovery, and conservation, as well as its place in de Kooning’s oeuvre and the UAMA’s collection. The treatment is still in progress, and the restored artwork is scheduled to be on view at the Getty Center from June 7 to August 28, 2022.

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

OLIVIA MILLER: We hear the security guards talking to one another on the walkie-talkie, saying that there’s a man on the line saying that he has a stolen painting. And I wish somebody could’ve seen us, because we just stopped our conversation and Jill’s eyes got big, and she said, “Oh, my gosh, are we gonna remember this moment for the rest of our lives.”

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with curator Olivia Miller and conservator Ulrich Birkmaier about a stolen painting by Willem de Kooning.

In 1953, Willem de Kooning exhibited a series of paintings on the theme of the woman. A year later in 1954–55, he painted Woman-Ocher, which was given to the University of Arizona Museum of Art in 1958 by its owner, Edward Joseph Gallagher, Jr. The painting was regularly shown at the museum until 1985 when a couple distracted a security guard, cut the painting from its frame, rolled it up, and surreptitiously took it away.

Thirty-two years later, in 2017, three men purchased the painting from the estate of a deceased couple and displayed it in their antique store where it was soon identified for what it was—the long-missing de Kooning. The University Museum quickly dispatched staff members to retrieve it.

Not long afterwards, the Getty was contacted, and Ulrich Birkmaier, Senior Conservator at the Getty Museum, and Tom Lerner, Head of Science at the Getty Conservation Institute, agreed to analyze and treat the painting.

I recently met with Olivia Miller, curator of exhibitions at the University of Arizona Museum of Art, and Ulrich Birkmaier to hear what they’ve learned about the panting during the restoration process, which is still underway.

Ulrich and Olivia, thank you for joining me on this podcast. Now, forgive me, Olivia, but I’m gonna spend the first few questions on materiality of the painting, the kind of questions that Ulrich, as a conservator is more prepared to answer, probably. And then I’ll circle back to you and to the ownership history of the painting.

Okay, Ulrich, Willem de Kooning painted the picture in question, Woman-Ochre, during the winter of 1954–55, at the height of his figure painting period. This is roughly 1948 to 1965. Describe the painting for us, both its formal and material properties.

ULRICH BIRKMAIER: So de Kooning painted Woman-Ochre, as you mentioned, in the winter of 1954–55. It shows a highly-stylized, abstracted, seated nude woman, facing the viewer squarely, with her arms to her size, emphasizing the square shape of the composition. Her head and face are distorted in a grimace, and somewhat less finished or fleshed out than the rest of the figure.

The figure is painted in hues of yellow, turquoise, red, green, and orange, and pretty much fills the canvas, which is about thirty by forty inches in dimensions. And it’s set against a neutral gray background. So what is interesting to me is the title, Woman-Ochre, because you don’t really see much in terms of ochre in the painting.

CUNO: Do you think he knew what he was saying when he said ochre? In other words, do he think that the kind of brownish-yellow colors that we see were ochre colors?

BIRKMAIER: Yeah, yeah. I think probably, the overall effect of having these different colors and hues set against each other—the yellow, the orange, the reds—sort of make for a somewhat overall ochre effect.

CUNO: In terms of how it was painted, how does it fall within his oeuvre? I know that subject matter-wise, it fits perfectly within the woman’s figure painting series that he painted; but in terms of the way it was painted, how does it fall?

BIRKMAIER: Yeah. I think it’s probably best seen and understood in relation or in the context of the other works from this very prolific period of the 1950s that has the subject of the Woman series. It’s a period that covers more than two decades, almost three decades, between the forties and the sixties, during which de Kooning explored the female figure, and rather obsessively so, one could say.

Early representations like the Queen of Hearts, from 1943 til 1946 is still very much traditional and figurative. But in 1950, there is a clear break, marked by Woman I, which is now at MoMa, which was painted over a period of almost two years, with the painting constantly shifting, changing, morphing. In fact, de Kooning was famously unable to finish a painting, often struggling with some details for months at a time.

CUNO: Did he paint from a figure?

BIRKMAIER: He did in some cases. We know that he used models, but he also took inspiration from ads, newspapers, magazines. So the faces, the distort, the grimacing faces are often inspired by magazine ads, actually.

CUNO: Now, I read in the mid-fifties, when he was painting this picture, that he was no longer building up his paintings in these distinct stages, wet over dry, but rather wet into wet. What does that mean, wet over dry and wet into wet? And what would make him want to make that change?

BIRKMAIER: Yeah, the traditional prescribed manner in which you build up a painting would’ve been wet over dry. So—

CUNO: He’d let one application of paint dry and then paint the second on top.

BIRKMAIER: Yeah, you build it up in layers. And this is not the case with the Woman series because you have a very gestural sort of action painting mode of technique. And so he used paints still in layers, but it could be applied very quicky, one session at a time. And then he would step back and evaluate the composition and maybe let it dry; but the next day or a week later, change the composition, and sometimes even erase some of the underlaying layers.

Now, this is not the case with Woman-Ochre, though. Woman-Ochre was actually painted very, very directly and with a relatively spare amount of paint, directly painted onto the pre-primed canvas.

CUNO: The figure itself is painted with Black strokes to distinguish the form of the figure from the body of the figure. Is the black the last thing painted on there, on the painting?

BIRKMAIER: So the black plays, of course, a very, very important role in de Kooning’s paintings. Sometimes, as it is the case here, you’re looking at paint, black paint, which in this case, is an alkyd paint. Sometimes you look actually at charcoal because de Kooning integrated charcoal, which is traditionally a drawing material, very, very frequently in his paintings. In the forties, he used charcoal more as a drawing, and then would later fill the canvas with paint.

But he increasingly used the charcoal, also in between layers, and sometimes even on top of the paints, to emphasize the outlines of the figure, as you can see in this painting.

CUNO: Yeah. I read somewhere that one can find still the fibrous particles of charcoal blended into the paintings. What would be the effect of that, the visual effect of that? Did it sparkle on the surface?

BIRKMAIER: Yeah, yeah. It would definitely have a distinct effect, since the charcoal really has a different surface effect than the paint. But I think in his case, he really used it to go back in, reemphasize some of the shapes, some of the outlines. And he did not use the charcoal as a traditional underdrawing, but rather as a vehicle to go in later and reemphasize, as I mentioned earlier, some of these shapes and outlines.

CUNO: So during this period, it’s also said that he adapted his painting methods and materials to the urban subject matter— the dense squalor of the city, as one author put it, and that this contrasts with the brightly-hued paintings of the 1960s, when he was painting in Sag Harbor on Long Island. Ulrich, do you buy that comparison between the grittiness and the brightly-hued paintings of Long Island?

BIRKMAIER: That’s a really good question, and I’m gonna have to think about this one. I mean, I’m not sure I would go as far as saying that he adapted his technique and material to the urban subject matter. Though, you know, maybe there is something to this statement.

We certainly do see a shift in the use of materials when he moves to Long Island. And there were probably several factors involved, like the change of light, the state of his mind, the shift towards more abstracted, fluid compositions. In fact, by the time de Kooning painted Woman, Sag Harbor, in 1964, he had actually discontinued his use of house paints, and instead was adding safflower cooking oil to artist oil paints. He used these rather unconventional materials to be able to have a longer working time. So it would stay wet for a long time. Instead, the traditional use of linseed oil would restrict him because it dried too quickly.

CUNO: Now, the painting was shown in an exhibition at MoMa, Museum of Modern Art in New York, in 1974. It was decided then to line the painting to address the damage it had suffered seven years earlier. How does one line a painting, and how can that address the damage of a painting?

BIRKMAIER: Yes, the process of lining, necessitated by the damage that you mentioned that had occurred during an exhibition, when the painting was sent on a tour of exhibitions in the late sixties, was addressed at MoMa in 1974. And it involved the relining of the painting.

So the secondary canvas that is adhered to the back of the painting acts as a support for the canvas that you see in front of us. And in this case, in 1974, a wax resin mixture was used to adhere the painting and support it with a secondary canvas.

CUNO: Yeah. So Olivia, thanks. You’ve been so patient for the set of questions that would come to you as curator of the painting. Tell us about the ownership history of the painting.

It was painted in 1954-55, and given to the University of Arizona Museum of Art by Edward Joseph Gallagher in 1958. What do we know about Gallagher? What’s his affiliation with the— your museum?

OLIVIA MILLER: Yeah. So the story about Edward Gallagher, Jr. is actually pretty interesting. He was from Baltimore. We know that he worked as an architect. And his connection to Arizona was initially that he liked to go out and visit.

So we know he went out to Arizona in 1915. He went to the Grand Canyon. And about a decade later, he was going out to Arizona more regularly, because he would go and he would work on a dude ranch near Tombstone. So Tombstone’s about an hour and a half from Tucson. So he had this connection to the Southwest, this love of Arizona. You know, especially coming from a big East Coast city.

Now, his connection to the University of Arizona specifically started in November of 1957. So he had read an article in Life magazine. This article was called “The Great Kress Giveaway.” And it was, of course, about the Samuel H. Kress Collection. So in the article, it was talking about this great act of philanthropy, where Kress was donating his collection all across the country. And the University of Arizona, at the time, had a loan of twenty-five paintings from the Kress Collection.

So this caught Gallagher’s eye, this act of philanthropy; and then his love for Arizona, it stood out to him. And so that same month, he wrote a letter to the University of Arizona president, Richard Harvill. And he said, “I love Arizona. I just read this great article in Life magazine. I understand you have part of the Kress Collection, as well as the Pfeiffer Collection.” So that’s a collection of 1930s and ‘40s American art. And he said, “Do you happen to have an contemporary French painting in your collection?”

So thankfully, somebody responded to him, because this little note could’ve easily slipped through the cracks. We still have it. It’s this little five-by-seven, you know, chicken scratch piece of paper. But the dean of the college of fine arts responded to him and said, “Thank you for your letter. No, we don’t have any contemporary French painting.”

CUNO: Why do you think he was asked about French painting?

MILLER: Well, six weeks later, he started donating it. So—

CUNO: Oh. So he had a collection of contemporary French painting.

MILLER: He— Well, he seemed to have a small collection. So he donated about sixteen paintings by artists who were either French or living and working in France. So Tinguely and Miró and Chagall. And he donated these works immediately, and started what was to become the Edward Gallagher III Memorial Collection.

So over the next twenty years, he expanded this collection at the University of Arizona Museum of Art to about 200 works of art. And this memorial collection, he established to honor the memory of his only child, who had died about twenty years prior, just shy of his fourteenth birthday, in a boating accident. And Woman-Ochre was a part of this collection.

So he almost certainly saw Woman-Ochre in Baltimore. We know that in 1957, there was an exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art of contemporary American artists, from the Martha Jackson Gallery. And that same year, he wrote to Martha Jackson and was pleading with her to sell to the painting. Apparently, she had told him that it was part of her personal collection and it wasn’t for sale. And he really urged her and said, you know, “Please do your part to build this collection in the Southwest. Do your part to honor this young boy’s memory.” And she did eventually sell the painting, and then he immediately donated it to the university.

CUNO: So he never had it at his house.

MILLER: No. And that’s a really interesting thing about the memorial collection, is that he bought these artworks over the course of twenty years. And we have incredible correspondence with him. He’s really going around and hand selecting artwork specifically to come to the University of Arizona. I mean, he’s really making very specific decisions, because he really wanted this collection in the Southwest. He wanted students who didn’t have the means to travel to big cities to be able to see the art that was being created in big cities. So this was not his personal collection that he built up over the years and donated. You know, these were specifically selected.

CUNO: How was the painting received by the students and faculty of the university?

MILLER: They seem to have been really excited about it. We know that the university president thanked him for it. Along with donating Woman-Ochre in his particular set of gifts that he bought from Martha Jackson, we know he also donated a John Hultberg and a Morris Louis. And we know that the painting went on view to the public in 1958 at the museum.

So they seem to have been really excited about the painting and overall, really excited about Gallagher, because he wrote this letter, that initial letter, in 1953. And that was a time when the university was really trying in earnest to get a, you know, individual fine arts building. At the time, art classes were scattered across ten different buildings. There was a little art gallery in the library, but by now they had this collection.

And then you had the Kress Foundation, who had this promised gift of sixty-four objects that was going to come, but they wouldn’t give it until a building was built. So Gallagher, he came into the scene at a great time, where they were really trying to set aside a space to really build a strong collection at the university.

CUNO: Now, the painting was stolen the day after Thanksgiving in 1985. Tell us what’s known about the theft, how it happened, and what its effect was on the university and the museum staff, after that extraordinary story you just told us about how it was embraced by the faculty and the students at the university.

MILLER: Yeah. So what we know— Again, like you said, the day after Thanksgiving in 1985, we know it was in the morning. And the building was just starting to open up for the day. There was a man and a woman sitting outside in the courtyard, and a staff member entered the building and they came in behind him.

The security guards had not yet all taken their positions in the building.The man proceeded upstairs to the second floor and the security guard began upstairs to go take her position up there. But the woman stopped her to talk to her about the painting that hangs in the stairwell of the museum. We now know that that was clearly a method to distract her and prevent her from going upstairs. About five to ten minutes later, the man came back down and the couple left the museum.

And the security guard continued upstairs, walked through the galleries, and that’s when she realized that Woman-Ochre had been cut from its frame, leaving only the wax lining behind.

So by the time the security guards got outside, the car was gone. There was a witness who described the car as being a rust-colored sports sedan with louvers in the back window, but they weren’t able to get a license plate number. They did not leave behind fingerprints. And unfortunately, at the time, we did not have a video camera system at the museum. And so although the University of Arizona Police Department followed up with a number of leads and got a number of statements, the case went cold very quickly.

We know the director was quite obviously horrified. He was also really upset because he knew that the museum was vulnerable. But despite this, he still maintained a sense of optimism. You know, he said, “I think there is a good chance that the painting could come back.” And I really wish he would still be alive to be able to see it come back, ’cause he was right.

CUNO: What about the alleged thieves? What do we know about them?

MILLER: Well, what we know is the painting was stolen in 1985 and it was found in 2017, hidden behind the bedroom— Well, I say hidden. Hanging behind the bedroom door of a couple named Jerry and Rita Alter.

Jerry and Rita Alter were from New York. We know that Jerry worked for the New York City schools as a music teacher, and we know he retired fairly young. And he and his wife and their two children relocated out to Cliff, New Mexico. Cliff is a very small town. They moved out there in the late 1970s. Even now, it’s still fairly remote. There’s only a few hundred people who live there. So I can only imagine how small it was when they lived there.

CUNO: How far from the university is it?

MILLER: Cliff is about three and a half hours from the University of Arizona, and it’s about forty minutes from Silver City, New Mexico.

So they went out there in the late 1970s. They bought about twenty acres of land. They built a house there. Rita worked as a speech pathologist for the public schools. And Jerry, you know, we know he was a musician, we know he was a Sunday painter. His house was covered in his paintings. And we know they were very adventurous. They traveled to more than a hundred countries. They left behind all kinds of travel journals and photos. And we know they had family in Tucson.

CUNO: Now Ulrich, tell us about the theft of the painting and the effects of the theft on this painting itself.

BIRKMAIER: Yeah, the effects, the damage of the painting that was suffered as a result of the violent, rather violent 1985 heist or theft were dramatic and traumatic, as well. So when I saw the painting in, I think, 2018 for the first time, it was stretched onto a new stretcher, had a simple gold frame. But—

CUNO: Maybe you can tell us what a stretcher is.

BIRKMAIER: : A stretcher is a wooden support frame that is used to lend support to the canvas in order to be able to install it in a frame.

At the time of the theft in 1985, the painting was still glued to the secondary canvas that was applied during the 1974 treatment; but the thieves actually ripped the painting off the lining canvas during the theft.

CUNO: What would be the effects of that on the painting?

BIRKMAIER: Well, the effects were horrible. And so you actually see, as the result of the ripping the canvas off, cutting it out and ripping it off the lining canvas, you see these horizontal damages that are throughout the painting’s surface, with considerable amount of loss associated; but also some lifting of the paint, which to us, suggested that after the painting was pulled off the lining canvas in 1985, it was possibly rolled face-in, which caused some of the lifting along these horizontal losses that you still see.

CUNO: Yeah. Olivia, when did the alleged thieves die? And I say alleged because I think the case has not been closed. And what happened to the painting after their death?

MILLER: We know that Jerry died in 2012. And Rita died in 2017. So when Rita died, she had left the estate to her nephew. And her nephew from what I understand, came to the house, you know, dealt with some of the personal effects, and then ultimately, he needed to sell the house. And so he was working with a real estate agent and she called a store in Silver City, Manzanita Ridge, that’s owned by my three favorite people in the world, David Van Auker, Buck Burnes, and Rick Johnson. And she called them up and asked them to come and look at the estate because at their store, they sell antiques and high-end furniture and things like that. And so she invited them to come out.

So they were the ones who went out there and they were looking at a piece of furniture in the bedroom and they had to close the door in order to really get a good look at it, and that’s when they saw the painting hanging on the wall.

Ultimately, they ended up paying $2,000 for the whole estate. They packed everything into their truck, which I try not to think about too much with this painting, and they drove it to their store, which is located in downtown Silver City.

And they took Woman-Ochre out and had laid the painting against a pillar in the middle of the store. And you know, I should stress, they didn’t quite realize what they were looking at. You know, they certainly recognized the signature de Kooning, but knowing that Jerry had paintings all over the house, they thought that maybe he had done a study of one of de Kooning’s paintings.

It wasn’t until a number of visitors came into the store and said, “You know, you should really do some research on that. I think it’s a real de Kooning.” And when one person offered them $200,000 for it, that’s when they said, “Okay, it’s probably time to do some research.”

CUNO: What was the recovery of the painting like?

MILLER: Oh, dramatic. I start the story of the recovery, actually, back to 2012. This is where I really think it began. So I started at the museum in 2012. And at the time, we had another curator. Her name is Lauren Rabb. And she had just read a book about art crime I can’t recall which book. But there was a detail that stood out to her, where the author had mentioned, you know, after a few decades have passed, artwork, you know, stolen artwork can turn up.

And she said, “You know, it’s been almost thirty years since Woman-Ochre was stolen. Let’s look at the file, let’s read the police reports. Let’s call the FBI and remind them we’re still here.” I really credit Lauren with getting this whole thing going, because she’s the one who gave us the sense of optimism. You know, three decades have passed. Somebody could’ve passed away; this painting could resurface.

So even after Lauren left the museum, in 2015, we were still very motivated by her. And we decided to hold an art crime event to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of the theft. And so we hung up the empty frame. We gave a public presentation, talking about the theft. And we had Special Agent Meredith Savona, from the FBI art crime team, come out and talk about the art crime team.

And we had a lot of attendees come to the event. We got a lot of press. And it’s exactly what we needed for the painting to come back, because being stolen in 1985, there was nothing about it on the internet. You know, unless you were specifically looking at the National Stolen Art File, you would never come across this painting. And so we knew we needed to get the story out there. And that’s what we did.

So fast forward to August, 2017. I’m sitting in my office. I’m talking to Jill McCleary, who at the time, was the museum’s archivist, and she’s now the deputy director. And we’re chit-chatting, you know, and we hear the security guards talking to one another on the walkie-talkie, saying that there’s a man on the line saying that he has a stolen painting. And I wish somebody could’ve seen us, because we just stopped our conversation and Jill’s eyes got big, and she said, “Oh, my gosh, are we gonna remember this moment for the rest of our lives.” And the call gets transferred to me and there’s a man on the line, and he says—

CUNO: Where was the man calling from?

MILLER: He was calling from Silver City. Calling from Manzanita Ridge. So David Van Auker was on the line, and he said, “I have your painting.” He said, “I bought some items at an estate. I was doing research on them.” And he said, “I’m looking at an article from The Arizona Republic from 2015, and I’m looking at the painting in my store and,” he said, “they are the same painting.” And he said, “I want you to have it back. Let me know what I need to do.”

So you know, naturally, I was freaking out in my head, but obviously, trying to be realistic. First and foremost, I wanted to ensure that he was talking about an actual painting. Because we fairly regularly get calls from people who think they have, you know, a treasure that they found at a thrift store, and it turns out to be a reproduction of some kind. And so I wanted to be sure that this wasn’t a poster or something like that.

And so I asked him to send me detailed photos. I wanted the signature; I wanted, you know, the photos taken at an angle, so I could see the surface of the paint and try to get an understanding that there was some texture to it. And one of the things I really wanted was a detail of the lines, because he specifically said, “There are lines across the canvas. It looks like it’s been rolled up.” And that was a detail that really stood out to me.

CUNO: The lines were broken bits of paint?

MILLER: Yes.

CUNO: They weren’t drawn lines.

MILLER: No, broken— So as Ulrich explained, when they were peeling it from the wax lining, those cracks— So that’s what David was referring to. So he sent me the photos and— And honestly, we’re all losing our minds, because we know that this could really be the painting. And I asked him to send the dimensions, and he said, “Oh, it’s roughly twenty-nine by thirty-nine.” And I just said, “Oh, my God, we have to call the police.”

And so we called the University of Arizona Police Department. They came over right away. And we sent all of the photos to Meredith Savona from the FBI. And then we didn’t hear anything. And that was the longest night of my life, the longest night of David’s life. Because we were really panicked, you know? We thought, gosh, David sounds so nice. He sounds very genuine. He wants to return the painting. But at the same time, we didn’t know who he was. And we were also really afraid that he would start looking up auction records or something, and that this painting would end up getting held in court for years.

So it was the simultaneous elation, you know, that “oh my God, this could really be the painting,” and then the simultaneous feeling of dread that we might be so close, yet so far from actually getting the painting.

We did end up getting the painting, of course. So the next night, we were able to drive out to Silver City. And it was a very long day, a very long evening. There were some kinks in the road, in terms of getting access to the painting. But we got it. And we went out there and we stored it at the sheriff’s station. And I just— I’ll never get over it.

CUNO: So the painting was recovered in 2017, thirty-two years after it was stolen. How do you close that case?

MILLER: Well, you know, for the museum, the case is closed for us. You know, we wanted the painting back and we got the painting back, and it’s currently in the best hands possible. So for us, it’s the best possible scenario. In terms of the FBI, they have kept the case open. So even though they have released the painting to us, it’s no longer held as evidence, they have kept the case open. And I’m not sure why. They haven’t told us anything.

You know, I don’t know if we’ll ever know, first of all, exactly if they were indeed the people who stole the painting, and if they were, exactly why. It’s hard for me to get into the mind of why somebody would steal a work of art.

But what we do know is that they were very adventurous people. You know, all of the travels they did around the world. We know that Jerry loved painting. And we know that they had family in Tucson. So perhaps this was just, you know, another adventure to kind of check off on their list. It’s really hard to say.

It’s hard not to think that they could have been the thieves, especially because Jerry Alter wrote a book called The Cup and the Lip. And it’s a sort of semiautobiographical compilation of short stories that are all really bizarre. And one in particular is called “The Eye of the Jaguar.” And it’s about jewel thieves, a grandmother and a granddaughter, who go into a museum and steal an emerald. And there are some parallels to what happened at the University of Arizona. But the strangest and kinda most eerie part about the story is that it ends with describing how they got away with the theft, and that there are only two pairs of eyes there who are able to see this emerald.

So when we think about that and this painting hanging in their bedroom behind the door, it does make you wonder.

CUNO: Now, when and why did you contact the Getty about conserving it?

MILLER: We reached out to the Getty in 2018. So the FBI kept the painting— I mean, we had it in our possession, but they were holding it as evidence for about a year. So 2018, we were finally able to start making decisions about where it should go for conservation. And it was actually Susan Lake, you know, expert on de Kooning’s materials. She was the one who said, “You know, you might wanna contact the Getty and see if this is a partnership that you could arrange.”

And it was the most obvious choice for us, for a number of reasons. One is, we had lent a Pacino painting to the Getty back in 2012, for an exhibition, Florence at the Dawn of the Renaissance. And we were just so impressed with the really holistic approach that the Getty takes to their exhibitions, where there’s this harmony of art history and technical art history that come together in really creative ways.

Logistically speaking, it made sense because the Getty has everything. You know, all of the people are here, all of the equipment is here. We didn’t want the painting to have to bump around from, you know, a studio to be driven over for, you know, technical analysis and all of the resources are here. And lastly, and probably most importantly, apart from getting the object conserved, is we really wanna make up for lost time.

You know, this painting was stolen. The public was deprived of it for more than thirty years. And we want as many people to see it as possible. We want something good to come out of it. And we know that the Getty is really incredible at not only advancing the field of technical art history and getting new scholarship out there, but also disseminating this information in ways that is really accessible to the public. And so we know a lot of people will be able to come here and see it. Those who can’t come will be able to experience it in other ways. You know, digitally.

So for us, it’s truly the best scenario we ever could’ve hoped for. And we’re really grateful that the Getty took on this project.

CUNO: So Ulrich, you and your colleagues have been working on the painting for some couple of years by now, I guess. What’s the status of it? What was it like when you first saw it and what is it like now?

BIRKMAIER: Yeah. You know, first of all, Olivia, thank you so much for entrusting us with this painting. It really takes a village. And as you heard, the damages resulting from the theft are considerable and very complex. And so it took a lot of study—study of the materials, material analyses—and then hundreds of hours of careful consolidation of the paint surface. Both of which, you know, executed by my brilliant colleagues Tom Lerner, the head of science; but Laura Rivers, conservator here at the Getty has been spending hundreds of hours working on the surface, setting down paint along these horizontal damages that you see that were [inaudible]—

CUNO: Tell us what you mean by consolidating the paint surfaces.

BIRKMAIER: So as a result of the theft, you had all this paint on the surface along the horizontal lines, where you have losses of paint, where the paint actually lifted up. And so we have—

CUNO: Because it was rolled up.

BIRKMAIER: Well, it was probably rolled up. And if it was rolled up, it was rolled face-in, which caused the paint actually to sort of crush against each other and cause some lifting along these losses.

And so Laura spent a good amount of time during this past year under the microscope, carefully setting down every single flake of paint, bringing it back into a planar state, where you can see it now. So right now, it’s actually loomed out, if you will, on a temporary stretcher. The painting is flat again. All the paint that was previously about to flake is secured, and so we can now start the process of removing the varnish.

There’s actually a couple of varnish layers, one that was applied during the 1974 MoMa treatment. So there is a synthetic surface coating that needs to be removed, together with a more recent varnish that was probably applied by the thieves.

CUNO: Really? How can they know that? I mean, how do you know when in the process of ownership of the painting was it treated?

BIRKMAIER: We only know of the 1974 MoMa treatment, and we have very, very thorough and careful documentation of all the materials and techniques that were used during the MoMa treatment in 1974, so we knew what to expect, in terms of materials from that conservation treatment.

But what we found was an additional varnish, a natural resin, which could not have been applied by anyone else but the thieves or by someone who was working for the thieves. But with Jerome Alter being a Sunday painter, I would assume that it was probably him attempting these rather amateurish attempts at restoration.

CUNO: Yeah. What’s next for you in the conservation of the painting?

BIRKMAIER: So the next step, now that the surface of the painting has been consolidated will involve the removal of those varnishes, of those surface coatings that I just mentioned. And then we’ll move toward the phase of reuniting the cut tacking margins, the border that was left behind when it was cut out from its frame, reuniting these borders with the canvas in front of us. And which will probably involve relining of the painting. But then we’ll reintegrate those losses, so it’ll be inpainted. And so the healing process has started, and we’re a good way into the treatment.

CUNO: Olivia, what’s next for the painting for you?

MILLER: Well, we’re really looking forward to it going on exhibit here at the Getty next summer, and then we will bring that exhibition over to our museum at the University of Arizona. And once that exhibition is over, you know, we plan to reinstall it in the permanent collection galleries, where it always should’ve been.

CUNO: Yeah. Well, it’s an extraordinary story and it’s a fabulous painting. Congratulations to both of you, and thank you for sharing the painting with the Getty.

MILLER: Thank you so much.

BIRKMAIER: Thank you so much.

CUNO: This episode was produced by Zoe Goldman, with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Mike Dodge Weiskopf. Our theme music comes from the “The Dharma at Big Sur” composed by John Adams, for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003, and is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast platforms. For photos, transcripts, and more resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts/ or if you have a question, or an idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu. Thanks for listening.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

OLIVIA MILLER: We hear the security guards talking to one another on the walkie-talkie, saying that t...

Music Credits

“The Dharma at Big Sur – Sri Moonshine and A New Day.” Music written by John Adams and licensed with permission from Hendon Music. (P) 2006 Nonesuch Records, Inc., Produced Under License From Nonesuch Records, Inc. ISRC: USNO10600825 & USNO10600824

See all posts in this series »

Why would anyone steal this? I wouldn’t hang it in my garage!